Change. According to the dictionary, the word change when used as a verb means “to replace (something) with something else, especially something of the same kind that is newer or better; substitute one thing for (another).” I think we can all agree that change is necessary in order for us to evolve, improve, move forward, and to make better. The “how” part is where things get murky.

One of the most important things we must do when we have a concern and a desire to change something, is to look to our allies for support and attract the audience that would be best suited to help us achieve our goals and that align with our ideology. In this particular blog we are going to look at gender equality and how it plays into public policy, specifically environmental policy. Does gender have an impact on who is listening, who will advocate, and who will be more effective in translating ideas, concerns, and problems?

There has been a push over the past 25-30 years to evaluate, implement, and incorporate gender equality in politics in order to create a more level playing field. The need to have more women involved has become evident.

It is no secret that there are issues that impact certain groups of people more than others or that impact them differently. One of these groups is women. When analyzing environmental issues, it is evident that women are affected more than men. As a result, women tend to take environmental matters more seriously and it is of greater importance to them. Women are also connected to the environment in other ways including a shared system of oppression. “In an unequal society, the impact of environmental degradation fall disproportionately on the least powerful” (Norgaard and York, 507) which is to say that the abuses and trauma that the environment suffers is then displaced upon women as collateral damage. Both are victims of those in power which has been referred to as the “logic of domination” (Norgaard and York, 509).

It would not be a stretch or leap to then assume that women, because of their vulnerability to the health issues that ensue as a result of environmental damage, would have a greater stake in, and be better advocates for, environmental policy? But is that actually the case? Likewise, could it be said that a lack of women in rooms (a lack of gender equality) in matters where decisions regarding environmental policy are made is resulting in the escalation of environmental problems and the expedience of environmental degradation?

The number of women in environmental organizations and grassroots movements far exceeds that of men which is evidence of their understanding of its importance and their concern for the future. Women are more cognizant of the risks that are present and invested in taking action to mitigate what they know the future will hold.

One might ask, why aren’t men more concerned? Why are they not as worried? Why are men not making more of an effort to advocate? This goes back to some of my previous blogs where we discuss sexism and how it overlaps and interplays with the degradation of animals and the environment. “Sexism and environmental degradation reinforce one another” in the same the way that other patriarchal ideology reinforces itself in its intersectional appropriation (Norgaard and York, 508). Women are an “Other” category, just as nonhuman animals are an “Other “category, just as the environment (nature) is an “Other” category. It is no coincidence that some of the top contributors to environmental problems are capitalist countries. Rich capitalist patriarchal countries.

Continuing on with this line of thinking we can see how having fewer women involved in politics makes it easier for the men to continue to reinforce these types of oppressive ideologies. So, what has happened when women are more involved? There is data that provides substantial evidence that having more women involved in politics, “contributes to the development of state environmentalism” (Norgaard and York, 513) however, I think it is important to reiterate that this is within countries where women’s voices are valued. For example, there are countries where women may sit in positions of perceived power, however they have little say or opportunity to contribute in any way that will actually culminate in policy change. An example of this is a country such as Singapore where women hold only 4.3 percent of legislative positions and have an extremely low record of ratifying environmental treaties (Norgaard and York, 515). Norway on the other hand is a great example of a country in which female leadership has had an enormous role within its government and as a result, gender equality and environmental movements soared resulting in legislation that ratified ideology supporting gender equality and environmental action.

The difference between those countries (and others) is clear – women express a greater urgency to advocate for the environment because they are hyper aware of its impact. What is equally important to note is that where there is a lack of gender equality within government, there tends to be a ripple effect within those states that disperses that inequality into other aspects of society.

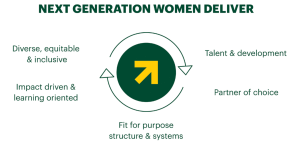

As I started digging into the topic of women (gender equality) in politics and the environment, one thing became abundantly clear, it is a system of many. It is a cycle of advocacy so to speak. Women in politics or women in power are never alone. They typically have an army of women behind them. They are often supported by grassroots groups, women’s organizations, and constituents in their local communities. One of the first groups that caught my eye is called “Women Deliver”. They are a group (of women) that organized in order to address gender equality and focus on a myriad of issues affecting women, one of which is climate change. They believe in an intersectional approach when examining issues pertaining to climate change. This group works in conjunction with 60 other groups and was the founder of a coalition called the SRHR and Climate Justice Coalition. They understand the idea that there is strength in numbers.

Organizations such as this are vital to policy change. While they may not be comprised of politicians, they can educate and help financially support those women that hold political power so that they can have a better chance at creating change. Women Deliver invests in policy change by developing partnerships, creating coalitions, publishing articles, giving a voice to underrepresented and marginalized groups, and raising awareness.

Another organization that I thought I should reference is Women Political Leaders referred to as WPL. It is an organziation of female political leaders advancing society. It is important to note that they are pushing for gender equality within all areas of government and their focus is primarily on health and immunization, but they do have a focus on sustainability.

“WPL strives in all its activities to demonstrate the impact of more women in political leadership, for the global better. To accelerate, women need three things: communication, connection, community.”

A very interesting article I read from Columbia University titled “Women and Gender In Climate Diplomacy” was of significant interest to me for the purpose of this blog because it examined women’s role in terms of climate diplomacy. They found that when women were involved in negotiations, that agreements were more likely to be reached. It also referenced that women were more successful in areas of environmental diplomacy because they were more active in organizing, and more in touch with their local communities. As a result, women are better able to access and harness public opinion and gain their support. Women exhibit a more personal and intent approach with their communities and constituents because they are closely affected by environmental issues.

Another important aspect that this article addresses, and was also prevalent in several of the websites I perused, was the emphasis placed on education and the need for the distribution of information both up and down the ladder. Education is integral to the success of women at all levels; a lack of it proving to further oppress. “Gender-focused work in Bangladesh shows higher rates of mortality during natural disasters for women, who, in certain locales, are not allowed to participate in public meetings and therefor are less apt to receive disaster and emergency preparedness information or receive medical and food assistance in the aftermath of such an event” (Jaffe and Nathanson, 3). This is an excellent example of how women are disproportionately affected as a result of the lack of gender equality permitted in their local meetings. It also demonstrates how these women would have a greater stake in their interest in environmental events. If provided with education/information and if given the opportunity to participate, these women could effectively help save lives. If we look further up the ladder, we see many of the women’s organizations and grassroots groups, offer support and training for those women wanting to be delegates. They provide the skills women need in order to be effective when they are granted a seat at the table to negotiate.

A common thread I saw in most of the material I read is that more gender analysis is required in areas of policy so that we can properly evaluate if there is a true and equal representation. Often times women are invited to the table, but they are not always permitted equal time to speak or be heard. It has also been noted that while registration to meetings might be comparable, the same cannot be said for the plenary meetings prior to the conferences or the amount of speaking time the women get as it is marginal in comparison to the men (Jaffe and Nathanson, 6).

When delving into Norgaard and York’s thesis, the most apparent connection is that which exists between women and the environment in terms of the impact their involvement in government can culminate in, which is change. It is a cycle comprised of women placed strategically at various levels of government, global/national organizations, and even in our local communities. The picture above illustrates this idea. It is imperative that we look to gender equality and its consistent presence within our state systems and processes.

In the OECD’s working paper No. 193, “Women’s Leadership In Environmental Action” (The Organziation For Economic Cooperation and Development) authors Helene Bendig, Sara Ramos Magana, and Sigita Strumskyte examine why, “Women’s participation in environmental decision-making is important for advancing both gender equality and environmental action. The presence of women in political decision-making is linked to more ambitious climate goals and policies” (Bendigi, Magana, Strumskyte, 5).

This comprehensive document covers five specific categories of analysis, all with statistical backing and they are:

- The Benefits of Environmental Leadership

- Women’s Environmental Leadership In Public Governance

- Women’s Leadership In Environmentally-Sensitive Industries

- Women As Environmental Leader’s In Society

- Policy Action to Promote and Measure Women’s Environmental Leadership

“The presence of women in political decision-making translates into more ambitious climate goals and policies (Mavisakalyan and Tarverdi, 2019[19]). For example, a study of European Parliament legislators over two legislative cycles found that while male and female legislators expressed similar concern for the environment, women were significantly more likely to support environmental legislation, even after controlling for political ideology and nationality (Ramstetter and Habersack, 2020[20]). A review of 1.2 million interventions in the UK House of Commons and 500 000 interventions in the US House of Representatives found that women of all political parties spent more time than their male counterparts addressing environment-related topics (OECD, 2021[2]) (D’souza, 2018[21]). A higher share of women in parliament has been linked to improvements on the SDG agenda (Mirziyoyeva and Salahodjaev, 2021[22]) and in environmental quality (DiRienzo and Das, 2019[23]). It has been estimated that countries with a critical mass of female legislators above 38% will experience increases in per capita forest cover (Salahodjaev and Jarilkapova, 2020[24])” (Bendigi, Magana, Strymskyle, 12).

This document is loaded with statistics that support the theories of Norgaard and York, providing data that gender equality (specifically the involvement of women) in government, has a direct effect on the priority of environmental concerns, and the extent to which legislation is presented and passed.

There is a clear and present link between women and the environment. Women continue to serve as affective allies to the environment because they understand and respect its beauty and resources, and they understand the devastation that its degradation and abuse can result in. The issue of gender equality must continue to be at the forefront of governments as they continue forward. Women acquiring equal space in rooms where negotiations happen, and decisions are made will help to ensure that all concerns are being represented.

Hi Teresa,

Thank you for sharing the video on President Sahle-Work Zewde. As the first woman to hold the position of president in Ethiopia, a country that has been known for its patriarchal culture and history of gender inequality, her commitment to women’s empowerment is especially relevant to Norgaard and York’s work regarding the relationship between gender and environmental policy. Undoubtedly, she is a great example of strong advocacy for gender equality and women’s empowerment and has the potential to inspire other African countries to follow suit and appoint more women to leadership positions. This can help to increase representation of women in politics and decision-making positions across the continent, which can lead to more inclusive and effective governance.

As noted by Norgaard and York, women are often disproportionately affected by environmental issues, and may be more invested in advocating for environmental policy as a result. While researching Marina Silva, I discovered a remarkable young woman from Los Angeles. Although not in a political leadership position, Nalleli Cobo has made significant contributions towards promoting healthy and safe neighborhoods while fighting against environmental injustice in her community. At the age of nine, she spoke out against harmful gas emissions from oil drilling, that were affecting her health and those of her community (“Nalleli Cobo – Goldman Environmental Prize”).

Cobo’s activism led her to discover that the health problems faced by her community were not unique but instead were part of a larger issue affecting other minority communities. This issue is a result of the disproportionate impact of oil drilling in these areas. To address this issue, she co-founded “People not Pozos”, an organization dedicated to securing safe and healthy neighborhoods. Her work as a co-founder of “People not Pozos” has been pivotal in raising awareness about the detrimental effects of oil drilling on the health and well-being of local residents. Cobo’s leadership and advocacy were also critical in the formation of the “South Central Youth Leadership Coalition”, which focuses on addressing environmental racism in their community and empowers young people to speak up and participate in environmental activism. Through her involvement with this group, Cobo has worked towards promoting community engagement and civic responsibility, inspiring young people to take action in the fight against environmental injustice (“Nalleli Cobo – Goldman Environmental Prize”).

Nalleli Cobo’s dedication to environmental justice is also evident through her involvement in STAND-LA, a coalition of community groups working to end urban oil extraction and protect the well-being of Los Angeles residents. As a valuable member of the group, she has made significant contributions towards the goal of banning oil extraction in the city. In fact, her advocacy efforts in 2020 were instrumental in prompting preliminary votes in the City Council in favor of a ban, a major accomplishment in the ongoing fight against environmental injustice. Nalleli Cobo’s inspiring story illustrates how women’s traditional roles as caretakers in the home and community can translate into powerful leadership roles in grassroots organizing efforts, as highlighted by Hamilton (1990) and cited in Norgaard and York.

Without a doubt, her impressive track record of accomplishments suggests that we will likely see her in a position of significant influence in the future. I look forward to the incredible changes that she will undoubtedly bring about.

If interested in learning more about Nalleli Cobo, visit the Goldman Prize website.

https://www.goldmanprize.org/recipient/nalleli-cobo/

Works Cited:

Nalleli Cobo – Goldman Environmental Prize. Goldman Environmental Prize -, 22 Sep. 2022, http://www.goldmanprize.org/recipient/nalleli-cobo.

Norgaard, Kari Marie, and Richard York. “Gender Equality and State Environmentalism.” Gender & Society, vol. 19, no. 4, SAGE Publishing, Aug. 2005, pp. 506–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243204273612.

Rose –

Thank you for your response and for sharing information about Nalleli Cobo! She sounds like someone to follow. I will definitely look at her work.

Teresa