When I was in 8th grade I was in a musical about the Greek Gods and Pandora’s box. The part I secured was that of the character “Hope”. I had only one scene at the very end. I (Hope) came out of Pandora’s box. I sang a song, and I can still remember the words. At 14 years old I remember it being difficult for me to get through it without getting emotional. These are some of the words:

“Hope is forever, trust is forever.

And then you can never go wrong.

Hope is the one bright thin ray of sunshine, the lifeline that keeps you warm.”

“The lifeline that keeps you warm….”

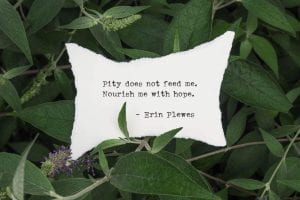

A common theme throughout the ecofeminist essays, journals, and other resources I have reviewed regarding activism is the idea that “where there is hope – there are possibilities.” (That is also my Twitter profile quote and has been since I can remember.) I think hope means different things to different people, but in essence what most people agree upon is that hope is an idea. It is the possibility that an idea can bring something: usually change.

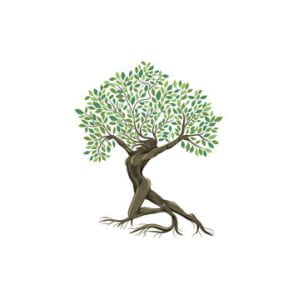

There are many connections that can be made between the shared oppression that women and nature share. Within certain circumstances, it is an almost circular or reciprocal relationship. When we look at communities where trees are felled, such as in Africa and India, it depletes the communities of so much. The kindling needed to heat their homes and cook their food, the shade provided, the natural protection that the trees secure is all stripped from them. The degradation of their natural surroundings is not only an assault to the tree itself, but to the ecosystem in which people inhabit. Both are continually victims of patriarchy.

Neither the trees nor women are given the consideration as a priority over economic profit. Those that prosper will continue to at the expense of so many women and nonhumans beings. So much life is cut short, hurt, sickened, and disqualified. As the forests are stripped of its trees, the communities are stripped of kindling to heat their homes and cook their food. The women see the devastation first because they live it. They do much of the farming so they are the first to see changes or threats to their harvest. They are the ones that fetch the water, so they are aware of how far they must go and how tainted the water is. They breast feed their babies and understand the danger that comes with passing chemicals and other contaminants from their own bodies to that of their children.

Women are the voices of the trees and the water because they know and respect the fact that they cannot live without either. None of us can. So they fight and become the voices of the trees like Wangari Maathai who founded the Green Belt Movement on Earth Day in 1977 (Maathai, 1). She was fighting this fight over fifty years ago in Africa. She was a woman who took action over and over again. She was both revered and denounced by her own government. In one moment, they praised her work distributing seedlings which culminated in the planting of millions of trees, only to be punished later for protesting a skyscraper that the President wanted to erect in a public park. Much like the trees that were hacked, the soil that was eroded, the resources that were depleted, Wangari was beaten and harassed and threatened not just as an activist but as a woman.

Wangari’s connectedness to nature was in part, through their shared oppression. Her for being a woman and the environment because its place (much like women) will always be second to that of the wants and needs of patriarchal society. She returned to nature its original offerings by organizing a movement to plant trees. It was a very full circle movement.

The Chipko movement is a very similar story but goes back to the 18th century when over 80 communities gathered forces to protest the King who permitted the felling of trees. Fast forward to the 1970’s and the Chipko movement was again ignited into action against the government that had planned to grant a section of forest to a sporting goods company. Women hugged the trees and would not leave and as a result, prevented thousands of trees from being destroyed.

These movements happened because women took a stand. They fought back against the situation that they found themselves in. Wangari would say that if you’re on the wrong bus – you need to take action and get out. Women recognize that while they may not have been given the proper information, training, education, resources, etc. it is up to them to inform themselves (Maathai, 3). There is a deep connection here that many women feel. A connectedness to that which provides for them, protects them, and nourishes them. Women recognize that to stay in the situation as it is means that nothing will change. Things will only get worse. Rather than blame the powers that be and rest on helplessness, they “speak truth to power” and in doing so empower themselves to create the change.

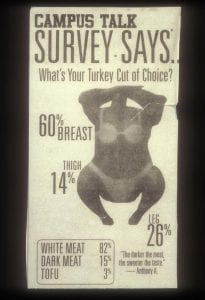

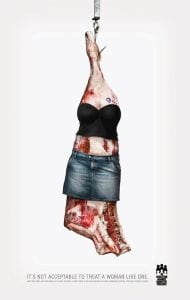

Women and nature share an oppression based on a lack of value. “Values have to do with the respect of each person – woman and man, each group, each culture, each ecosystem” (Gebara, 98). Gebara asks the question in terms of one’s religious theology, “What value is present in this or that theological tradition? How can it help us towards more justice and solidarity?” (Gebara, 98). I ask this question – What value is present in this or that societal ideology? What value is present in this or that governmental structures, procedures, and policies? What value is present in this or that corporate capitalist nomenclature? What do THEY value? How does one find value in a world that doesn’t value them?

When we evaluate situations such as Standing Rock where indigenous people fight against the mining/drilling of their land that brings upon them not only displacement but violence, we are reminded of that system of hierarchy once again. Who and what is valued more than something else? In a video about gendered impact and violence against the land, Gloria Chicaiza said “we speak for the birds, animals, fish , and other life forms”, it is a part of who they are. When they are stripped of these things, or when they witness the degradation of nature, they “feel it in their mind, bodies, and souls” because they are connected to it. They are one.

Beyond the scope of the material deficits, cultural losses, ecological destruction, is something vital. The loss of purpose and acknowledgement. The feeling of desperation, despair, isolation, nothingness, and neglect. In such circumstances people have cards stacked against them that they didn’t even play. The choice was never theirs. If it was, do you think that women would choose to allow their children to swim in garbage pools in Brazil to look for cans as a source of income? That is not a choice. That is desperation. The child may know nothing more, however that is only because they were never afforded possibilities. This type of degradation and disempowerment is an assault to a person’s sense of being and creates feelings of shame. Scholar, writer, and artist Leanne Betasamosake Simpson said, “I am not murdered, I am not missing, but parts of me have been disappeared and I remain a target, because I was a Native woman” (Simpson, 92). In that moment we can see the clear correlation between a woman who has had parts of her depleted or remain hidden as a result of oppression, much like a forest hast lost its trees. As people get worn down, they can lose part of who they are. They can separate from parts of their identity.

This is where hope comes in. Ivone Gebara said, “Without hope there is not life” and she was right (Gebara 101). It starts with an idea. In Africa it started with a seedling. That seedling was not just a seedling. It was far more than that. It represented an idea that could lead to change. It was a possibility. From there women took charge planting millions of trees. Initially they did not think such things were possible without education and technology, but they persevered. They were saving the forest and in turn the forest was saving them.

“When we plant trees, we plant the seeds of peace & hope.”

~Wangari Maathai ~

Check out this website called “The New Humanitarian” and read about Sheila Watt-Cloutier and her activism in Canada and about the John family and how the Yup’ik have been evicted from their land as a result of climate change.

It is worth the read!

The other day I was thinking about how I am short. I am 5’2”. I stood on a small step stool I have in the kitchen in order to reach something. It is about a foot in height. When I stand on this, I am at about the same height as my husband who is 6’ 3”. I stopped and looked around. I am always shocked at the view from up there. (I am also usually very upset at all of the dust I can see that I normally don’t. Sometimes ignorance really is bliss.) Then I started to think about intersectionality. I thought about what my husband is able to see and has access to versus what I see and have (or don’t have) access to. In this moment, not only do we not share the same gender identity, but we do not share the same perspective in the kitchen. I may think our kitchen is spotless, however he may not. He has the ability and access to see things that I cannot (without the help of my stepstool) so our daily line of vision and perspective will always be different. Get where I am going with this? I can utilize his ability to see things that are higher and use that information to my advantage. I can ask him to access that information for me and likewise he in turn can help me obtain that information and also share in the cleaning. (You can surely bet he will help.) If we fail to acknowledge the ways in which we are different and use them to our advantage to help one another, we will have an increasingly dirty home.

The other day I was thinking about how I am short. I am 5’2”. I stood on a small step stool I have in the kitchen in order to reach something. It is about a foot in height. When I stand on this, I am at about the same height as my husband who is 6’ 3”. I stopped and looked around. I am always shocked at the view from up there. (I am also usually very upset at all of the dust I can see that I normally don’t. Sometimes ignorance really is bliss.) Then I started to think about intersectionality. I thought about what my husband is able to see and has access to versus what I see and have (or don’t have) access to. In this moment, not only do we not share the same gender identity, but we do not share the same perspective in the kitchen. I may think our kitchen is spotless, however he may not. He has the ability and access to see things that I cannot (without the help of my stepstool) so our daily line of vision and perspective will always be different. Get where I am going with this? I can utilize his ability to see things that are higher and use that information to my advantage. I can ask him to access that information for me and likewise he in turn can help me obtain that information and also share in the cleaning. (You can surely bet he will help.) If we fail to acknowledge the ways in which we are different and use them to our advantage to help one another, we will have an increasingly dirty home.